In her autobiographical A Memoir: People and Places, Mary Warnock devotes a full chapter to our former Prime Minister, a personage that she encountered on several occasions. This will be a long post but Warnock's observations amount to a wonderful piece of character assassination.

Philosophers from Warnock's generation who were based at Oxford and Cambridge were very accomplished at witheringly eloquent put-downs but generally confined their verbal cruelty to slagging off each other. So this is an exception.

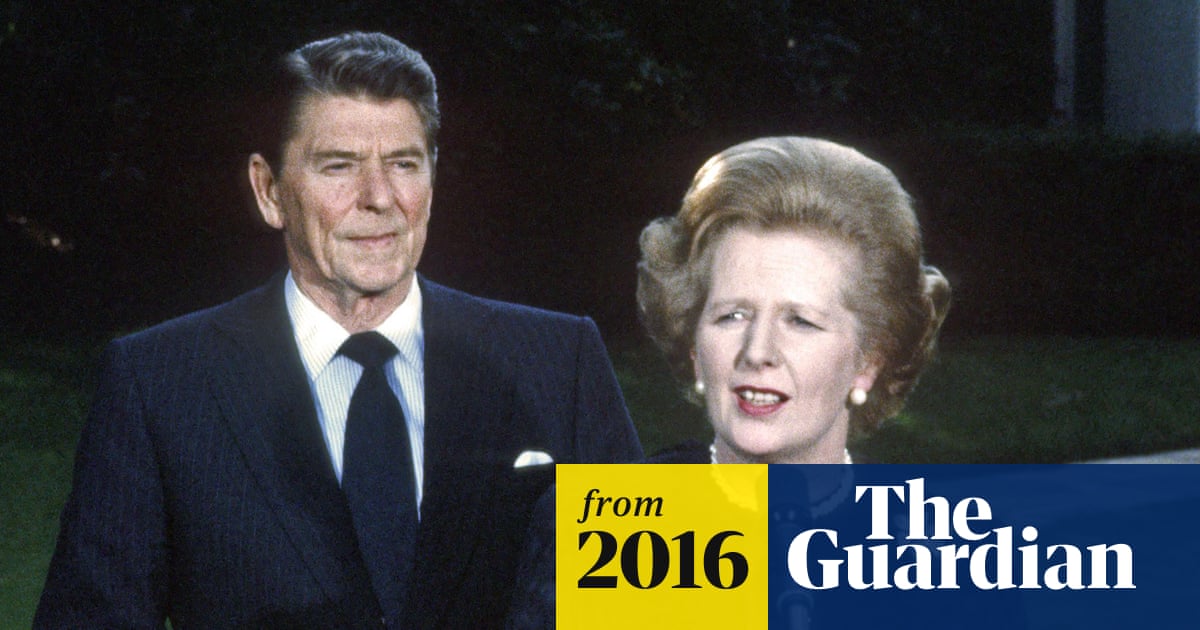

But anyway, having been disconcerted at an informal pre-lunch party by Thatcher’s inappropriately regal bearing, 'total absence of warmth', ‘sheer rudeness and bad behaviour’, and unimpressed with her ‘gaudy clothes‘ and ‘rampant hairdressing‘ (apparently, her famously bouffant hair looked 'ragged' from the back), Warnock proceeds to offer this description of a speech made at a later meeting of the Independent Broadcasting Authority:

'As soon as we sat down to lunch, and while the dishes were still being served, she started to speak. It must have been before she was taught, by those responsible for her packaging, to drop her voice by nearly an octave, and there were no dulcet tones. There was not even the air of the exasperated primary school teacher, with difficulty keeping a grip on her patience, to which we were becoming accustomed on television. Instead, she spoke loudly, in a high-pitched and furious voice, and without drawing breath (or so it seemed, though she was able to swiftly eat up her lunch at the same time). Her theme was the appalling left-wing, anti-government bias of the independent television companies, and of the authority itself...Her new plan she stated, was to curb the media, and compel them to present news and current affairs in accordance with government wishes.'

When a suggestion was made to her that such a policy would be damaging to the freedom of the press, 'she swept it aside, and declared that the People were not interested in the freedom of the press, but only in having Choice (it was the first time I had heard this formula); and choice meant having available a variety of channels, all of which were truthful and encouraging. Nobody mentioned Stalin, but he was in everyone's mind.'

And there's more. This is about a subsequent address Thatcher made at a Vice-Chancellor’s lunch:

‘Almost as she hurried in with her little partridge steps, the Prime Minister began to rant against the universities, their arrogance, elitism, remoteness from the People, their indifference to the economy, their insistence on wasting time and public money on such subjects as history, philosophy and classics…she did not stop for more than two hours [and] no single one of her hosts could get a word in.’

The Vice-Chancellor was her husband Geoffrey, another noted philosopher, who was similarly shocked by Thatcher’s ‘deep philistinism, amounting not just to a failure to understand but a positive hatred of culture, learning and civilisation.’

Reflecting on these episodes, Warnock remarks [the word in block capitals is hers] that 'I think that she simply did not know how to behave and was in some way LOW, eventually confessing that whenever she thinks of her, she cannot help but recall ‘a particular electric blue suit‘ which ‘expresses directly, like a language one has always known, the crudity, philistinism and aggression that made up Margaret Thatcher’s character.‘

A little further on, Warnock writes that she was concerned by an 'aspect of the Great Educational Reform Bill of 1988. The consequence of the 1988 Education Act in so far as it was concerned with school education, was to introduce the idea of competition between schools, and choice for parents. The league tables showing the academic achievements of schools alongside one another were supposed to enable parents to choose the best schools. The free market would operate. Schools which performed badly would not be chosen by parents, and so would ultimately wither away. This was the original idea. (no one gave thought, apparently, to what would happen to children who were pupils at these bad schools while they were in the process of withering away).' [Warnock herself was worried about the impact on the education of children with special needs].

'This part of the 1988 Act was derived largely...from a personal vendetta of Margaret Thatcher's, this time against the teaching profession. Teachers could be judged, she thought, by the academic results of their pupils; the operation of the free market would succeed in the end in eliminating those schools where the teachers were bad; or market competition would cause those schools to get rid of their bad teachers and employ good ones, so that they would become good schools. This was the theory, enthusiastically propounded by Kenneth Baker, and close to Margaret Thatcher's own heart.'

Later in the chapter and still on the subject of the 1988 Great Educational Reform Bill, and the establishment of the University Funding Council, Warnock notes that the latter new body was dominated by representatives from the business world who were largely in thrall to the view that the goal of higher education should be to satisfy the needs of commerce and industry. The preceding White Paper had made it clear that it was up to Whitehall and not students to decide which subjects were worthy of study: ‘The Government considers student demand…to be an insufficient basis for the planning of higher education. A major determinant must be…the demands for highly qualified manpower.’ In a nutshell, the purpose of universities should primarily be to serve ‘the world of business’.

Warnock goes on to conclude that ‘the condition to which higher education was reduced was, I think, one of the worst effects of Thatcherism…the concept of learning, the respect for higher education for its own sake, as something intrinsically worth having, an essential part of any civilised society, had been thrown out; and this largely because of her own detestation of academics.’

Fast-forward to the present and not much has changed. Quite recently we have had Farage being dismissive about the social sciences, for example.

Will therefore let yet another philosopher, the estimable Martha Nussbaum, have the last word:

‘We increasingly treat education as though its primary goal were to teach students to be economically productive rather than to think critically and become knowledgeable and empathetic citizens. This shortsighted focus on profitable skills has eroded our ability to criticize authority, reduced our sympathy with the marginalized and different, and damaged our competence to deal with complex global problems.’