I'm guessing this film won't have much about their legendary offstage activities ..you know tiddlywinks, Scrabble and the like

www.expressandstar.com

www.expressandstar.com

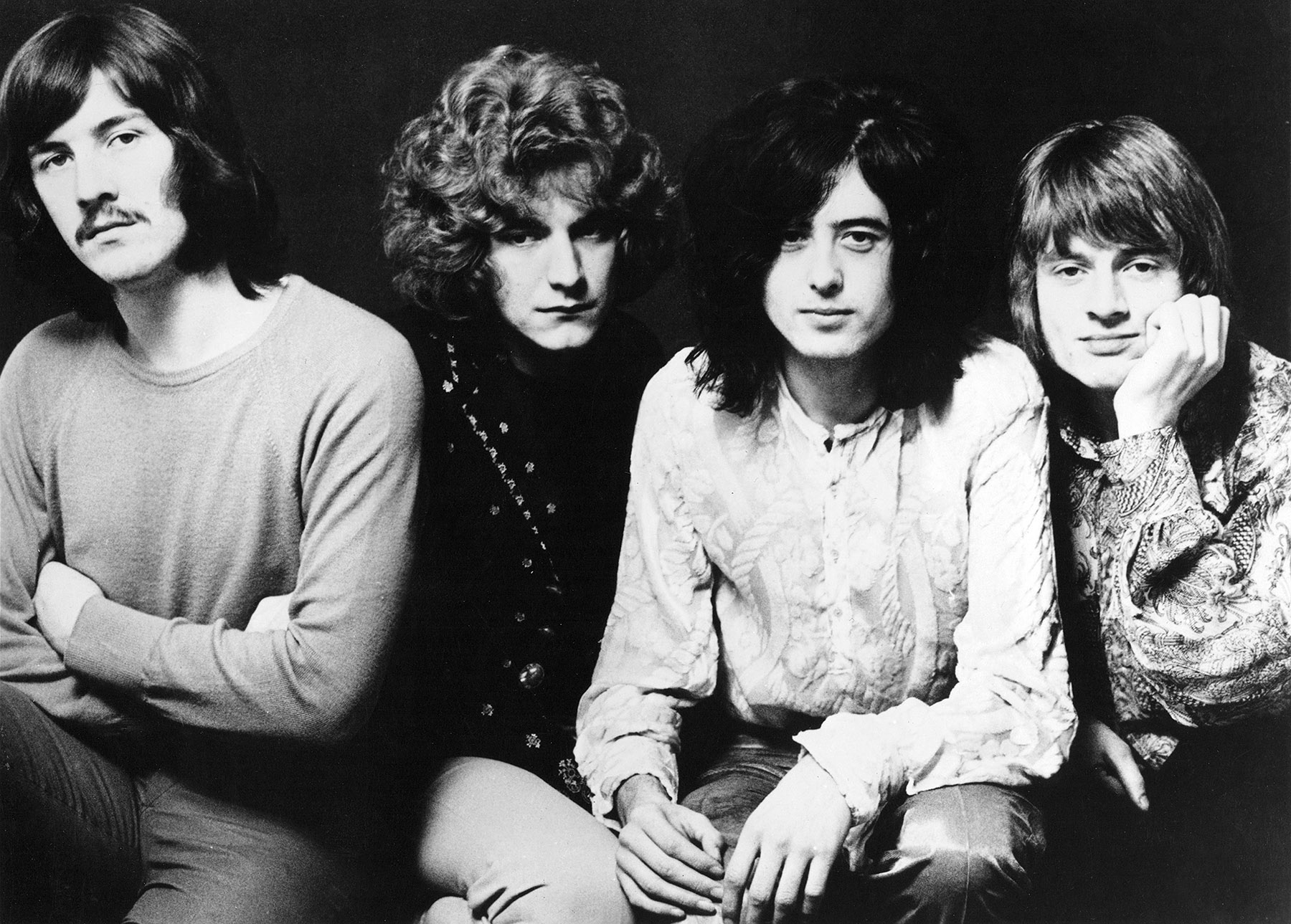

Celebrities gather to celebrate premiere of 'Becoming Led Zeppelin' - a band with strong ties to the West Midlands

Musicians and celebrities gathered for the LA premiere of Becoming Led Zeppelin, the first official film about the legendary band, at the TCL Chinese Theatre this week.